My works draw on the grandiose, rock-strewn mountain landscape where i am living.My paintings, sculptures, and videos reflect almost my life and organic under-standing of the land whose real and symbolic value i measure.

HAMLET HOVSEPIAN

Facebook Badge

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

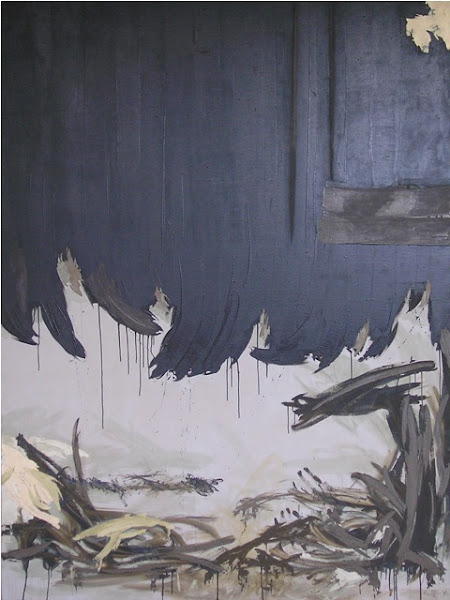

picture O-21 1996

oil bronze aluminium metal stone wood

BY "Georg Schöllhammer"

Georg Schöllhammer

The rediscovery of an unknown masterpiece of conceptual cinema from the former Soviet Union: Hamlet Hovsepian’s »Washing Hair, Biting Nails, Yawning«

This 13-minute black-and-white film, made in 1975 in the small village of Ashnak in the Caucasus, on the periphery of the Soviet Union, begins with a close-up: the camera looks down onto the head, bent forward, of a man washing his hair – as if it were following the stream of water pouring over this head, apparently tipped out from some sort of container. The scene is a simple one. And yet behind Hamlet Hovsepian’s apparently harmless view of this activity is concealed an entire repertoire of powerful visual gestures: one is put in mind of the close-ups of working hands that became conventional formulae in Soviet films, of cleansing rituals like those documented in early ethnographic cinema, of baptism. The opening scene in Hovsepian’s performance documentation and conceptual art film »Washing Hair, Biting Nails, Yawning«, which depicts an everyday action in minimal fashion, without any allegorical trimmings, thus becomes an allegory of an existential condition.

The sequence that follows is a rhythmically constructed, abstractly composed series of images of quarter profiles, back views and detailed studies of a young man’s shaven head. Each frame is constructed two-dimensionally and in balanced grey tones. With this sequence of images, full of direct and indirect presence, Hovsepian again opens up a whole network of cultural associations for the viewers. A network that ranges from the body-scan photography of 19th-century positivist psychiatrists, the film documents containing the rabble-rousing racial ideology of the Nazis, the objectively documentary camera of the liberators of the concentration camps, concealing the horror behind similar pictorial formulae, and the Stalinist repertoire of images of the »traitor«, to the abstractions of Surrealist photography.

After these severe, symbolically charged and ascetic series of cuts, the film swings about to theatrical scenery – both in structure and mood. In front of the neutral backdrop of a wall, as if positioned there for a casting session, sits a man whose clothing and behaviour easily identify him as belonging to the milieu of Soviet critical intellectuals of the seventies. He is practising yawning in an exaggerated stage fashion. After the half-portrait of this man, showing a close-up of his face, that of a woman biting her nails is projected.

Unlike the faces of the man washing his hair and the man with the shaven head, those of these two people are turned towards the camera. They carry out their gestures and actions, all indicative of boredom, in a space charged with attributes of fashion and thus with time, and in a manner that allows physiognomic and stylistic classification. In a time-stretching choreography, the images of the yawner and the nail-biter alternate repeatedly – the images stay the same, but mutate nonetheless. They do not do this in the »classical« procedures of cinema – montage, editing, camera work, etc. – but materially: Hovsepian over- or under-exposes the film, lets it fade or slides black in front of the scene. In a deconstructive procedure analogous to the analytical procedures of experimental films elsewhere, one that takes into account the physical materiality of the film, Hovsepian distracts attention from the constant repetition of the motif – and the way it is overworked -, drawing it instead to the kinds of abstract images which the material itself projects onto the screen: shadows, superimpositions, highlights, errors in exposure, scratches, smears, blurs. This play of light on the screen in the end finally blots out the reminiscences of scientific films and their viewer constructions from the scenes showing the gestures, almost rigid in their repetition, of the yawner and the nail-biter, who position themselves before the camera as in historical studio photographs; it makes one forget the similarity of Hovsepian’s scenes to the technique used by this genre to document patients with psychoses; the resemblance of the depiction to early slapstick cinema dissolves. Hovsepian’s succinct observation of the everyday as a theatrical installation does evoke these associated images, but also allows the viewer to see the performers themselves as observers of this game with light and media. In its static, minimal takes, the film tells of an almost existential state of being set back. A feeling that would seem to have parallels in the life of its maker.

In the late sixties and early seventies, Hovsepian, who was then living in Moscow for a while, was in close contact with the left-wing aesthetic avant-garde in the capital. But he differed from it in his artistic approach. As opposed to aesthetic critique as work in a symbolic space that draws on the formal apparatuses of everyday and ruling culture, as it is always incorporated, reflected, in Moscow conceptual art of the time, in his film, which was made after he had left Moscow, Hovsepian inserts the social back into the subjects. This conjuring trick - which, in one bold move, dispenses with the oppressive burden of the hollow ideological kitsch of the bureaucratic culture of the Brezhnev area as an aesthetic projection surface and withdraws to the stage of abstract, everyday acts - and the completely unspectacular camera work have no parallel anywhere else in the Soviet counter-avant-garde of those years.

In the mid-seventies, Hovsepian returned to Armenia, to his studio in the small village of Ashnak, where he has lived ever since. There, in voluntary reclusion, he began consistently to create a body of conceptual works. As well as this film, which was conceived and filmed on one of the rural afternoons in Ashnak, and is today only available as a copy urgently in need of conservation, he created a number of installations and interventions on an equally reduced scale: a few plants in plastic bags in front of a house wall, newspaper that draws a line in the landscape along a slope at the foot of Mount Aragats. And later, he produced a series of paintings following the new conventions of Perestroika art. In the Caucasus, Hovsepian is seen by many artists of the middle and younger generation as one of the erratic avant-garde figures of the seventies. (1) Arman Grigorian once paradoxically and ironically called Hovsepian’s studio »The Kitchen« of the Soviet Caucasus. Not completely without reason. This one film alone places the filmmaker Hovsepian in a genealogy in which the films of the New York underground are also inscribed. Washing long hair, biting nails, yawning – gestures of deviance that positively reverse the image of isolation current among cultural pessimists, as a seizure of space in a world of standardization, of the mass society, as cultural critics called it in those years. Hamlet Hovsepian’s film is not only the result of a small revolt against the deadly passivity of this society. The reduction it carries out, its silence, gives a universal turn to the meaning of emptiness, to the abstract space, and the frequently extended time.

Translation: Timothy Jones

SPRINGERIN 1 / 2004

PICTURE H-16 1992

OIL BRONZE ALUMINIUM ON CANVAS /200x150

by "Susanna Gyulamiryan" on my solo exhibition RE-TURN

Susanna Gyulamiryan

At first glance Hamlet Hovsepyan’s work might appear fragmented and moving in disparate directions: video, performance, work with the land, abstract expressionism in painting and land-art. All this vast variety of possibilities, all this list of terms have found their place into his artistic tool box and can be explained by means of a "laissez-faire-ness" in the production of artistic images in the post-Soviet milieu, which itself is the result of the long hoped for destruction of the repressive concept of historical style that has been limiting artists’ freedom.

Hovsepyan uses this “freedom" with both a technical fluency and a naive noble heartedness in relation to the "gifts" that have been allotted to his time and the diversity of possibilities presented by a world that is ever changing and renewing itself. A world endowed with ever more sophisticated technology and opportunities for the most refined artistic desires. Because, for him all media serve the all important ideological constant of semantic permanence that is so valuable for an artist of significance and meaning, completed in the unity of life and art and in a wider sense in the identity of thinking and being.

Citing, or more likely, imitating the views of the historical avant-garde, he sees the authenticity of the creative existence in the return to the single natural world, to the primary evidence, where the whole world is seen as a work of art. From this point of view he transforms a natural event into a certain continuum not in the sense of a mimetic act or a simple imitation of this point of view but of a constant re-turn to nature’s foundations, to a complete existence that is not torn to pieces by another artist or the logic of the contemporary world. Today, the reliable objects of identification, it seems, are lost, individualisation is delayed and handicapped. And such an organisation of human communities, where each individual is concentrated on itself with the break down of normal human relations and loneliness can be diagnosed as an important symptom of contemporary culture. The choice of the solitary estranged existence in the desert that surrounds his native village and which he practically never leaves, from the point of view of a way of life reminds one of the above mentioned atomisation of existence. However, this solitude seeps through not into a real but a utopian paradigm: that it is precisely in such an existence that the artist can see the realised utopia of his own personal life. The topos of a harmonious and “safe” existence acquired by the artist is a real geographical location – the Armenian village of Ashnak. Here, he has established for himself the boundary of a way in to the world with, what is for him, its unbearable social control in favour of a way out into individual independence, where the paradigmatic cognitive model of his selfhood is built on self-actualisation and self-purification.* The artist turns away from a culture that distorts its foundations with a “social mandate” placed upon the process of artistic production, dominated by the phantoms of the mass media where there is no place for any attempt to transform one’s own life into a work of art, which is what Hamlet is passionately trying to do, and it seems, is achieving within the social and geographical framework set out by him.

Ashnak’s rocky landscapes or the fossilised “views” of the surrounding world that often feature in his video works, can, however, elicit a feeling of homelessness, transience, a pure “a-topia”, a complete absence of place. But this transience appears as a nostalgia in the present, which the artist overcomes with a romantic utopianism, in which he continually creates his individual and idiosyncratic hopes. His way of life is a therapy of individual frustration, where Hamlet, liberated from the world, accomplishes an act that refreshes his insight and self-revelation and repeats this semantic order, practically in all his works.

The paints that he uses are also sanctified with the light of a certain truth. Hamlet sees colour in absolute terms. The active use of bronze and aluminium should create the effect of an "aura" that has something akin to the techniques used in icon painting. In his works he also researches processes that have a place in the natural world, where living creatures are turned into inorganic remains and vice versa – inorganic remains are returned back to organic life. The static character and twinkling rhythm of his ascetic video-landscapes bring over both the dynamically ecstatic in the manner of Jackson Pollock and a meditatively transcendental outburst, a striving to merge with nature while supporting his favourite idea of birth which is death. Thus, the realised utopia of Hamlet Hovsepyan’s private isolated existence, of completing his imagined cycle, which re - turns the lost link with the messianic that unites unbroken time.

A bare foot that leaves no footprint is another symbol used by the artist in one of his videos. And this symbolises the constant movement and striving towards the unified Image, towards all the new works of human utopia, where the most cherished social hopes are manifested.

"Matjaz Gruden " To be or not to be...

Hamlet Hovsepyan

Matjaz Gruden

To be or not to be...

Hamlet Hovsepyan is yet another Armenian painter (hat took part in the Telekom International Painting Weeks. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Erevan. Before coming to Pinm his only travel “abroad”, had been to Moscow, where he had worked and collaborated with other Soviet artists. Upon returning to Armenia, he moved io a small village of Ashanak some 80 km from Yerevan where he put up his studio. Living in an environment with practically no communication with other artist, he continued his artistic work, spanned among painting, colours and, in order to survive, (arming, lie has sustained with a lot of support ofhis wife and his children. In last fifteen years two poles of Hamlet's artistic work can at least be detected. Painting is one. He has been trying to merge painting with three-dimensional interventions, using the objects from farm-life .surroundings, or from another of his great admiration, the film. His second artistic pole certainly is sculpturing or space installations, where object found in his environment are being used. He uses parts of agricultural machinery, tractors, farm tools, stones, tree-branches and merges all into organic union, that .sometimes becomes a new performing machine. They may evoke visual sensations by themselves and sometimes, when in motion, they produce visual effects, too. Hamlet expresses great interest, almost an obsession with technology and machines, and his ability to produce "new machinery" based on rules in painting and his intuition. This is the field of creativity that seems closest to him and he feels strongest there.

His paintings are abstract and full of gestures; the use of colour is reduced. By the end of eighties and at the beginning of nineties mostly black and white paintings prevailed with minimum of other colours and with the use of tiny Armenian letters. Hamlet combines gesture, surface and lines into an image well balanced. He uses printer's paints mostly. Silver and gold offset colours appear frequently. These paintings could be classified as. "one peace- formation due to their . complexity and monumentality.

In mid nineties he started to change his palette by using even more silver and mixing it with green. It seems there are several reasons, one of theme being certainly the wish to merge film and painting, needing the silvery basis for projecting the film picture on later. The colour, on the other hand, can symbolise the incandescent Armenian countryside. His artistic development leads him to the two-part composition and to excessive use of silver and gold. The paintings have been loosing the monumentality of the older paintings; the idea is mediated only through projection of the film image. Unfortunately it is too dependable of the darkened room. The other parts of the paintings have more or less stopped existing, or have become attendants of the newly produced moving images inside the painting.

Hamlet's trip to Piran and meeting other artists and their work made confrontation and comparison possible. Many questions and dilemmas have been disclosed. He tried to get the answers during his stay already. One month is not enough for such complex answers, unfortunately. But in Hamlet's case the famous question: "To be, or not to be..." by his Danish namesake, due to his creative energy, diligence or better professionalism; can in no case be asked neither by himself nor by anybody else.

Mednarodni Slikarski tedni, Celje (Slovénie) 1999

PICTURE N-11 1995

145.5x192cm/OIL BRONZE ALUMINIUM ON CANVAS

PICTURE M-46/2004

200x200cm/OIL ALUMINIUM BRINZE ON CANVAS

Connaissez-vous Hamlet Hovsepian, peintre ?

| |

par Denis Donikian Dans le cadre de l’Année de l’Arménie en France seront exposés à Quimper, fin janvier et début février 2007, quatre peintres venus d’Arménie : Krikor Khatchadrian, Armand Krikorian, Mher Azadrian et Hamlet Hovsepian.

|

EXHIBITION IN QUIMPER,FRANCE

WORK BY HAMLET HOVSEPIAN

PICTURE 50/2000

127x189 cm/OIL BRONZE ALUMINIUM ON CANVAS,127*180

No comments:

Post a Comment